Background of the graphic design

I was never drawn to the subject of graphic design when I did my foundation year of art studies, I found the technical requirement for control and precision daunting and I disliked the thought of having to please a client. Later on when I was hired as a darkroom technician and layout artist for a screen printing company, I learned and appreciated the skill involved in the graphic arts industry, however I disliked many of the inane designs we were asked to print.

This attitude precluded me from participating in private industry, but it presented no hindrance to working for public organisations who generally felt more comfortable dealing with an artist who was willing to extend their practice beyond the usual fine artist exhibiting at a private gallery model, and rather than hiring a graphic designer who came with a big price tag and an overly commercial view of their craft.

In the 1970s the idea of the arts connecting with the community had evolved to the degree that money had started to flow into projects such as the student union funded Union Arts Activities press at R.M.I.T. University. The poster workshop, which encouraged students to become involved in learning the craft of screen printing was one initiative they funded, but most of the work produced by the resident artist was the production of posters publicising Union Arts events such as an artists on campus scheme and rock music nights.

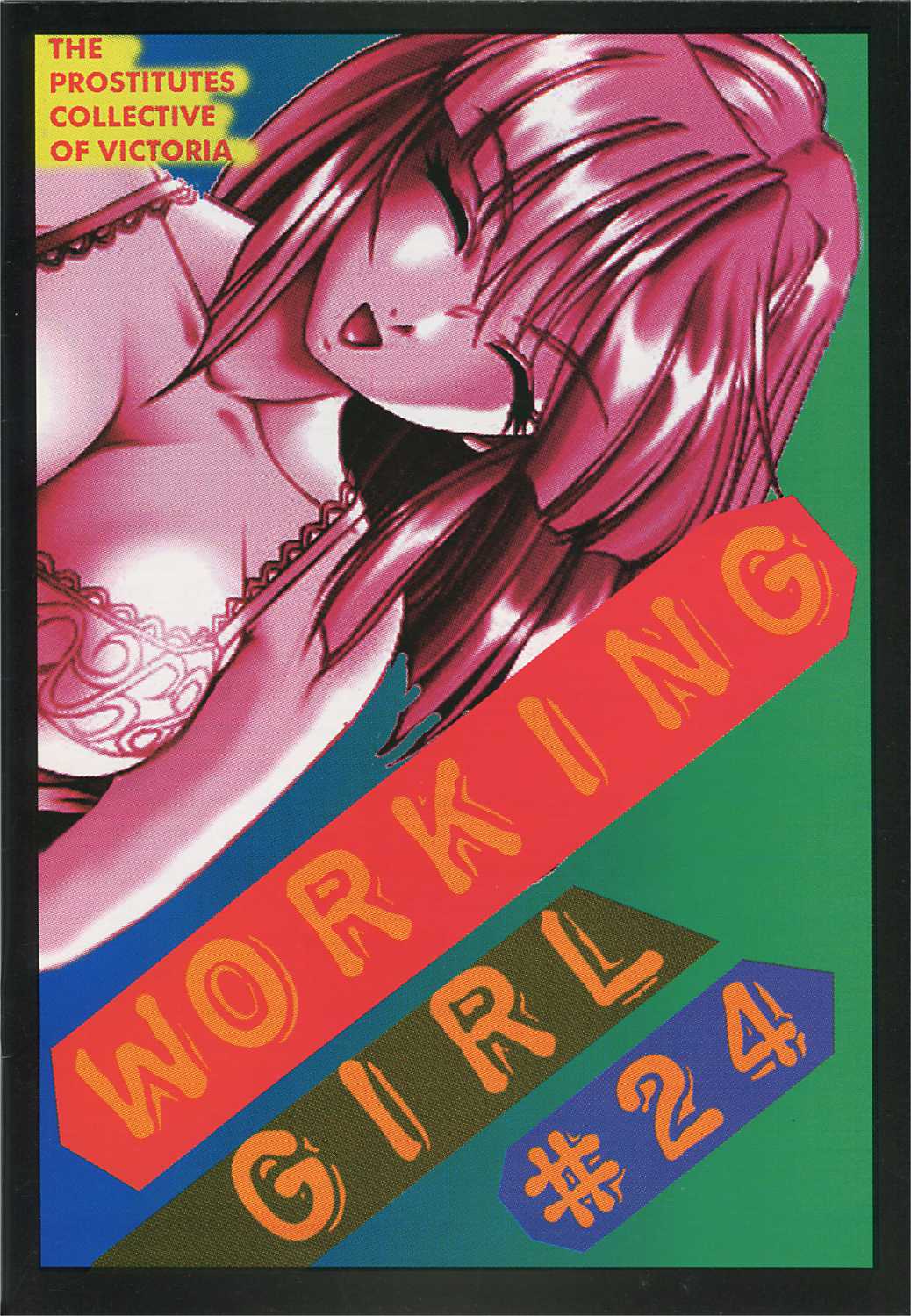

The Prostitutes Collective of Victoria, who represented and advocated on behalf of sex workers, was another progressive organisation who encouraged artists to become involved in the production of their magazine Working Girl, Worker Boy. The graphic illustrating this essay, Working Girl #24, is typical of the cover art when I edited the publication, as are these examples.

The use of a cheap and easily learned printing medium like screen printing also led to the formation of left wing activist presses such as Redletter which was used for the production of a poster advertising the first Melbourne Fringe Festival. And screen printing was also the obvious medium for the do-it-yourself punk ethos of the 1970s when the Melbourne inner city creative community saw visual artists, musicians, film makers and writers collaborate on projects such as the use of studios as events spaces.

The other great democratic communications medium for bringing ideas out onto the street was graffiti. Up to the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period when grafitti started to develop an aesthetic recognisable today, most of its use was overtly political and sloganistic. A large sized paint brush and a can of white enamel paint was the standard approach but Bozone, a Neo-Dadaist group of provocateurs, was one of the first groups in Melbourne to recognise the potential of the stencil as a fast hit-and-run spray paint technique.

In the period I have discussing, art practice in Melbourne briefly took a detour away from gallery based art. This phenomenon can be partly explained by a skepticism of the value of art as an expensive commodity which is only affordable to a wealthy minority versus a community art which becomes de facto common property. There is still a residue of the latter that exists today but the private ownership of art is as firmly entrenched as ever.

Several examples of the work I made during this period have been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, not because they are inherently good, but because the curators have understood that these works were part of an interesting brief historic shift to the democratisation of the visual arts.